Here’s a quick list of what we’ve covered.

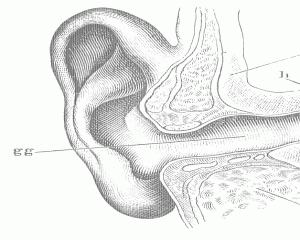

(1) Many argue that ocularcentrism—or the primacy of the eye, vision, and metaphors of light (over, say, the ear, listening, and sonic metaphors)—dominates Western culture.

>>> Question: How do you critically respond to ocularcentrism through audio work?

(2) After the popularization of sound inscription and reproduction (in the late 19th century), sound became information.

>>> Question: What kinds of problems (e.g., legal, cultural, political, or aesthetic) emerge once sound becomes information?

(3) Sound (especially the voice) is often associated with presence or authenticity (e.g., proof someone is here or alive).

>>> How does the reproduction of sound complicate that association?

(4) Listening is a learned and embodied practice. R. Murray Schafer argues for critical listening, and he gives us the terms keynote sound (e.g., background sound), signal sound (e.g., foregrounded sound), and soundmark (e.g., a community sound).

>>> How do we learn to listen? Consider your audiographies, which suggest that—through habits—we become so familiar with many sounds (especially keynote sounds) that we learn to ignore them.

(5) We’re also determining how to learn about media theory and history by actually composing new media. For example, consider our “Interactive History of Sound Reproduction” as well as our use of WordPress and Audacity.

>>> When composing with new media, how does visual culture shape our understanding of audio and sound?

(6) When media and inscription technologies change, so do stories, storytelling, and the way we learn.

>>> In a switch from visual media to audio, what story elements stick? Which ones are altered? And how do we keep people’s attention on audio?

Next up: our eight case studies, materialist theories for studying technologies and media, how to tell a story with audio, and the “audiovisual litany.”